TORONTO, April 26, 2016 – In 1442, Shinto priests in Japan began keeping records of the freeze dates of a nearby lake, while in 1693 Finnish merchants started recording breakup dates on a local river. Together they create the oldest inland water ice records in human history and mark the first inklings of climate change, says a new report published today out of York University and the University of Wisconsin.

The researchers say the meticulous recordkeeping of these historical “citizen scientists” reveals increasing trends towards later ice-cover formation and earlier spring thaw since the start of the Industrial Revolution.

Sapna Sharma, a York University biologist, and John J. Magnuson, a University of Wisconsin limnologist, co-led an international team of scientists from Canada, United States, Finland, and Japan looking at this early data. Their findings are published in Nature Scientific Reports.

“These data are unique,” says Sharma. “They were collected by humans viewing and recording the ice event year after year for centuries, well before climate change was even a topic of discussion.”

Torne River, spring 2003 in Tornio. Photo by Terhi Korhonen

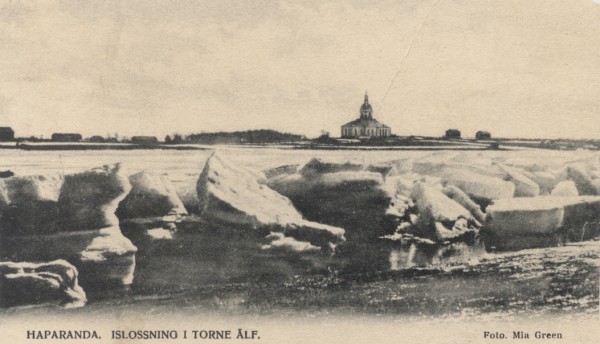

The records from Lake Suwa in the Japanese Alps, says Sharma, were collected by Shinto priests observing a legend about a male god who crossed the frozen lake to visit a female god at her shrine. A local Finnish merchant initiated data collection on Finland’s Torne River because the river, and its frozen-or-thawed status, was important to trade, transportation, and food acquisition.

Lake Suwi's Omiwatari, when the ice heaves in a line across the lake

Ice seasonality, or when a lake or river freezes over in winter or thaws again in spring, are a variable strongly related to climate, says Magnuson. And while such a long-term, human-collected dataset is remarkable in and of itself, the climate trends they reveal are equally notable. “Even though the two waters are half a world apart and differ greatly from one another,” he says, “the general patterns of ice seasonality are similar for both systems.”

For example, the study found that, from 1443 to 1683, Lake Suwa’s annual freeze date was moving almost imperceptibly to later in the year – at a rate of 0.19 days per decade. From the start of the Industrial Revolution, however, that trend in a later freeze date grew 24 times faster, pushing the lake’s “ice on” date back 4.6 days per decade. On the Torne River, there was a corresponding trend for earlier ice break-up in the spring, as the speed with which the river moved toward earlier thaw dates doubled. These findings strongly indicate more rapid climate change during the last two centuries, the researchers report.

In recent years, says Magnuson, both waters have also exhibited more extreme ice dates corresponding with increased warming. For Lake Suwa, that means more years without full ice cover even occurring. Before the Industrial Revolution, Lake Suwa froze over 99 per cent of the time. More recently, it does so only half the time. A similar trend is seen with extremely early ice breakup on Torne River. Extreme cases once occurred in early May or later 95 per cent of the time, but they are now primarily in late April and early May.

Postcard from 1906 taken in Happaranda

“Our findings not only bolster what scientists have been saying for decades, but they also bring to the forefront the implications of reduced ice cover,” says Sharma. The consequences of less ice span ecology, culture and economy. “Decreasing ice cover erodes the ‘sense of place’ that winter provides to many cultures, with potential loss of winter activities such as ice fishing, skiing, and transportation.” Less ice and warmer waters also lead to more algal blooms and impaired water quality, she says.

The Priest Mr. Kiyoshi Miyasaki pointing out some of the records on lake ice and the omiwatari. His data sheet summarizing the records are on the table. Photo taken Nov 3, 2005 by JJMagnuson.

The team of researchers say they are planning follow-up studies to better understand the ecological consequences of the big changes in these two water bodies.

*Photos are also available:

http://news.yorku.ca/files/Spring-2003-in-Tornio.-Photo-by-Terhi-Korhonen-1.jpg

http://news.yorku.ca/files/Lake-Suwis-Omiwatari-when-the-ice-heaves-in-a-line-across-the-lake.jpg

http://news.yorku.ca/files/Postcard-from-1906-taken-in-Happaranda.jpg

York University has always been known for championing new ways of thinking that drive teaching and research excellence. Our 52,000 students receive the education they need to create big ideas that make an impact on the world. Meaningful and sometimes unexpected careers result from cross-discipline programming, innovative course design and diverse experiential learning opportunities. York students and our 283,000 alumni worldwide push limits, achieve goals and find solutions to the world’s most pressing social challenges, empowered by a strong community that opens minds. York U is an internationally recognized research university – our 11 faculties and 25 research centres have partnerships with 200+ leading universities worldwide.

Media Contact:

Sandra McLean, York University, 416-736-2100 ext. 22097, sandramc@yorku.ca